Memorizing answers for a test is not the same as being taught by those with practical experience

If they can pass the tests, they get the certificate.

That seems to be the mentality of management people in the field of education today. SATs, standardized student level test, and the like seem to be the ruler by which a school, teacher, educator or, in our case, the flight instructor is measured. If the instructor’s students consistently pass the required tests, he is considered a good instructor. Little or no consideration is given to whether the students can apply the knowledge they were given. Certain professions, such as law with the Bar exam, medicine with internship, residency and certification in various specialties, and accounting with required practical experience, all stress the ability of the students to apply their knowledge and to learn under experienced practitioners after receiving their college degrees.

While obtaining my formal education in the 40s and 50s, and then my pilot and instructor certificates in the 60s, one important thing stands out in my mind: I learned the practical application of knowledge, not through textbooks, but through the interface between other students and me. Above all, I learned from teachers, professors and persons experienced in the field of study, that education goes beyond the books and tests. Some things cannot be put in writing: They must be experienced. In lieu of experience, they must be discussed with individuals with experience. What I’m trying to say is there must be a human element in the educational process.

Let’s examine what the average student pilot goes through in obtaining his or her private pilot certificate. First of all, the lack of formal ground schools in most areas means the student will prepare for the knowledge test using some type of video or computer program. It is my opinion that these programs are excellent for preparing for the written exam, but that is all. Since the FAA provides all the questions and answers for the knowledge test, it is not difficult for providers of these electronic ground schools to gear a course strictly to the written exam.

In preparing to write this, I reviewed one of the better known of these electronic ground schools for the private pilot. I could find only three short subject areas that were not directly related to the knowledge test or practical test standards. Unfortunately, as experienced and veteran pilots know, the requirements of the knowledge test and PTS are not sufficient to produce a truly proficient pilot. Another disadvantage of electronic ground schools is that, all too often, they lead students to nothing more than the rote level of learning. In other words, they concentrate on the answers to the questions rather than the substance of the material. The student now takes the FAA knowledge tests and comes out with a good grade. But does that student really know the material? The unfortunate answer is, probably not.

There is also a problem stemming from the fact that the student, while doing this unsupervised home study course, was also taking flying lessons. Under today’s situation, the flight instructor is, in all probability, a reasonably inexperienced pilot. But, the instructor’s training has been so geared to passing tests with a minimum of flight time that the sum total of his or her aviation knowledge again involves only what is contained in the knowledge tests and PTS.

For the student, what is missing in this equation is exposure to experience. While being prepared to pass knowledge and flight tests, which they will do and become fully licensed private pilots, most of them will not be exposed to the knowledge and wisdom of experienced pilots. Keep in mind that on a flight test the applicant is evaluated on ability to meet the standards. Technique makes no difference as long as the results meet standards. Experienced pilots will tell you that the old cliché, “there is more than one way to skin a cat,” applies to aviation in spades. A good pilot will be aware of the various techniques available to handle various situations, perhaps never using more than one; but knowing the others may help to develop what works best. An experienced instructor can help develop a technique suitable to a student by knowing various ways to handle a situation. A less experienced instructor does not have this option, knowing only what he or she was taught.

Here are two obvious situations where various techniques are available:

First, the crosswind approach and landing. What is best? The crab or wing low procedure or a combination of both? Full flaps, partial flaps or no flaps? Power on or power off approach? Approach speed?

Next, normal approach and landing. Power off or on, on final? Where to apply flaps? How much flap to use? When to lower the gear? Touchdown speed?

There are also some knowledge areas where time spent with experienced pilots can go a long way toward producing a safer and more proficient pilot. Here are two examples.

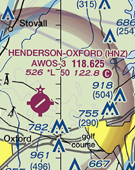

Learning how to evaluate the information in a weather briefing. Inexperienced pilots are somewhat brain-washed to accept and act on forecasts and weather reports exactly as they get them. Experienced pilots can give you some good advice on how to evaluate these forecasts and reports, and make more valid decisions.

Learning how to handle wet or icy runways. Not many low time pilots have experienced hydroplaning or know much about it. The experienced pilot probably has experienced it and has respect for it. He can explain the value of being able to touch down at the lowest possible speed.

So what can the fairly low time or inexperienced pilot do to fill this void in aviation education? In my day it was not hard. On weekends, there was always a group of pilots sitting around and talking about flying, and the group always included some highly experienced pilots. What I learned while sitting in, and mostly listening, at these sessions has been invaluable in my aviation career.

While these hangar flying sessions are not as common as they used to be, they still exist, and I urge you to seek them out. Ask around. There may be a small airport in your area where there is a regular hanger-flying group. If so, try to drop in and participate. Also, if you know some reasonably experienced aviator, try to draw him or her into a conversation where you can ask questions. The opportunities to talk and listen to experience are still there, just harder to find.

Now, one final but very important piece of advice. You may hear a lot of suggestions and ideas. Take all of them with a grain of salt unless you know the speaker, because there will be both good and bad advice. Don’t accept any of it unless you are given a good explanation of why it is a good idea. When you hear different ideas on the same procedure, listen to the “why” and make your own judgment. When I am asked for advice, I always tell the recipient the “why” of my method. I then emphasize that, if I haven’t convinced him my way is better, then stick with what he is doing. Listen to the different techniques and ideas, and the explanations. Then roll them around in your brain and decide what is best for you.