The Voice of Experience

It has been my pleasure in the past few months to administer instructor renewal flight tests to three gentlemen, each of whom has been instructing for more than 50 years. My 39 years of instructing pale in comparison.

What interested me most were the comments that each made regarding the changes he had seen over the years in both pilot training and pilot proficiency. While the tests were administered individually, the comments and insights were amazingly similar, almost as if they had all gotten together and planned them.

Their major complaint? Modern training is geared too much to the flight test and flying by the numbers to the detriment of basic stick and rudder skills. This manifests itself in several ways. The most obvious is a lack of precision. The Practical Test Standards outline the minimum standards, such as plus or minus 100 feet of altitude or 10° of heading, required by a pilot today to qualify for a certificate or rating. Unfortunately, pilots and most instructors are satisfied if these standards are met. As one of the gentlemen above, who was an instructor pilot in World War II, put it: “The standards may be good enough for earning a certificate, but I would hate to have a pilot who was satisfied with these minimum standards flying close formation with me.” Another one put it another way: “I don’t know why they build the center of the runway — nobody uses it anymore.”

It is obvious to them that few modern pilots have experienced the pride and exhilaration that comes from flying an airplane with a high degree of precision. Unfortunately this same attitude leads to more dangerous weaknesses, foremost of which is poor rudder usage, which leads to poor yaw control. These veteran instructors note other problems, such as the touchdown speeds on landings. According to them, most pilots no longer land the airplane — they run it onto the runway. As one of them put it, a little more dramatically: “They make controlled collisions with the runway.”

They are concerned that full stall landings are seldom taught and much less used. Full or semi stall landings are harder to teach and master and are therefore not taught when a run-it-on-the-runway technique is easier to teach and learn. The idea that one flying technique is picked over another because it is easier to teach and learn than a safer technique is totally repugnant to me.

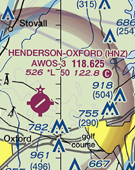

Another complaint from these “ancient pelicans” is that new pilots and many older pilots quickly lose their basic navigation skills. The last time many of our newly minted pilots filled out a complete flight log for a trip was on the flight test. After that, pilotage and dead reckoning skills are thrown out the window in favor of modern electronics such as GPS. Ask a pilot a year after his latest flight test to fly a cross-country flight without the use of electronic nav aids and he will probably get lost. There are all too many instances of pilots having radio or electrical failures and not being able to continue the flight safely. In many cases they run out of fuel, resulting in an off-airport landing. Of course this landing is often unsuccessful because of their run-it-on-the-runway landing technique.

So what advice do these veteran pilots offer?

- Work on your precision. Do not be satisfied with anything less than plus or minus 50 feet of altitude and 5° of heading. On crosswind takeoffs, set up a crab to stay aligned with the runway after lift off.

- Get your feet back into your flying. Good rudder control means the ball in the middle except when using a slip, such as in a crosswind landing. Remember the pilot sits on or close to the center of gravity and does not feel the effects of yaw as much as that poor passenger in the rear seat. The best way to have a passenger throw up in your airplane is to be skidding it all over the place. If you are a sloppy pilot, the sick passenger may be your fault.

- Don’t be satisfied with a landing unless the centerline of the runway is between the main wheels. This includes crosswind landings.

- Learn how to touchdown within 200 feet of a predetermined spot at or near the stall speed. If you don’t hear the stall warning going prior to touchdown, your touchdown is too fast.

I can assure you that working on these things, even if it means spending some money and time with an experienced instructor, will make your flying much more enjoyable and satisfying. More important, though, it will make you a better and safer pilot. The rewards are infinite.