Do It Yourself Weather

In my flying career, I have seen tremendous strides forward in almost every aspect of aviation. Many are obvious, such as turbine engines, and pressurized light twins and single engine airplanes. In general aviation, the biggest improvement has come in navigation capabilities. The move from Four Course Ranges, to VOR, to VOR/DME to Loran and now GPS has tremendously improved the ease and versatility of navigation. Unfortunately, in my opinion, it has not done much to improve safety in general aviation.

As a matter of fact, it probably has been a detriment to safety, because all too many of us, from airline pilots to brand new private pilots, have allowed basic navigation skills deteriorate to a dangerous level. I have encountered many high time, professional pilots who no longer can use VOR effectively. They fail to realize that the modern navigation systems should be aids to basic navigation skills, not crutches.

Now, what does all of this have to do with weather? Well, it is simple. Again, in my opinion, I think the greatest potential advance in aviation safety, over the past 30 years or so, has been the tremendously increased availability of weather data through computer access.

In the not too distant past, the prevalent and accepted method for the general aviation pilot to receive a weather briefing was through a phone call or visit to a flight service station. The flight service specialists were, and are, well trained and do an excellent job within the restraints of the system. Unfortunately, they are very limited, by their operating procedures, in the extent to which they can disagree with official forecasts and reports. In addition, to paraphrase an old saying, “their days can be hours of sheer boredom interspersed with moments of sheer chaos.” When the weather is CAVU all over, they have very little to do, but let the weather go sour and they are up to their eyeballs in calls for briefings. In the latter case, the problem for the pilot is either inability to get through for a briefing, or the specialist must do a hasty job in order to serve as many pilots as possible.

Nowadays, all the information that is available to the FSS, and more, is available to most pilots in the comfort of home or office. All that is needed is a computer and a modem to access free DUAT at an 800 toll free number. Internet access is not even required, and it is paid for by the FAA. However, with Internet access there are many other sources of complete aviation weather, some free and others at a modest charge. Being a cheapskate, I use DUAT, but you all have your options.

Of course, the trick is how to use all of this information, and my formula follows.

First off, find out what is available. This is easy. Draw up a complete route briefing. Don’t do it for a route from New York to Denver. You will find yourself with 30 pages plus of information. Rather, pick a direct route for two locations no more than fifty miles apart, one of which provides a terminal forecast or TAF. Also, if your provider offers a plain language translation, request both the FAA format and the plain language interpretation.

Next, go through this briefing with a fine-tooth comb. Learn what is available. I know you have all heard about such things as Area Forecasts, Terminal Forecasts, Metars, Pireps, Notams, FDC Notams and the like, but how many have you actually seen and studied? You will also find other reports that you may not have heard of. I will leave it up to you to discover these. Do this several times, until you are totally familiar with all the available information. Then, and only then, will you be prepared to do your own weather briefings and analyses.

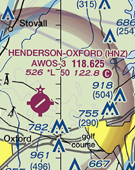

Here are examples of what can happen with a briefing if you do not know what to ask for. In the process of writing this article, I got several telephone briefings for a flight from a major airport to a nearby feeder airport, 30 miles away. Initially, I did not receive the following information. The lights on a tower 2,500 feet AGL, four miles from the destination airport, were out of service and so was the AWOS at the destination airport. Finally, a chance of thunderstorms was forecast, but I was not told that a pilot report was available that stated a thunderstorm with cloud-to-ground lightning had been observed several miles northeast of the destination airport. I then asked the briefer if there were any NOTAMS or PIREPS that might affect my flight, and he informed me of the above. Of course, I already knew about them through a computer briefing. However, without the computer briefing, I would have also asked for them, because I know what information is available and where, and I asked the briefer to check it.

So, even if you do not have computer access, find a pilot friend who does and ask him or her to draw up and print a route briefing. Then study and learn it, so you know what is available and can ask pertinent questions of the briefer if you are not satisfied with what you are told.

One of the most frustrating and discouraging things I encounter on a flight test is when I ask an applicant a specific weather question, such as the surface winds at the proposed destination airport, and I get the answer, “the briefer did not give me that”. My immediate reaction is, why didn’t you ask for it? The briefer may not consider calm winds important enough to mention, but it would be necessary to compute an accurate landing distance. If you use telephone briefings, it is important to know what information is available so you can ask if something you consider important is omitted. On the whole, briefers do an excellent job, but you can help them to do a better job by being knowledgeable about reports. That’s where studying computer generated briefings becomes important.

Once you have a good briefing, you must then know how to analyze it. Obviously, the most important reports in a complete briefing are the area and terminal forecasts. One well kept secret concerns the three important airmets that always are published. They are Airmet Sierra for IFR conditions and mountain obscurations, Airmet Tango for turbulence, and Airmet Zulu for icing conditions. These three Airmets are always available, even if to say that no significant turbulence, IFR conditions, or icing are forecast. If somebody tells you there are no Airmets, they are misinformed.

The problem with forecasts is that none of them are valid. They are basically educated guesses by meteorologists and their computers. You, the pilot, have to validate them. If you learn nothing more from this article than how to validate a forecast and use it, I will have added to aviation safety. You do this by comparing the forecast weather with the actual weather. Consider the following information from a terminal forecast:

9AM 6000 BKN, 8000 OVC VIS greater then 6 miles

11AM 5000 OVC, VIS 5 miles in light rain

2PM 3500 OVC VIS 5 miles in light rain

5PM 800 OVC VIS 2 miles in rain.

You plan to depart at noon for a two and a half hour VFR flight, arriving around 2:30 p.m. It looks pretty likely that you can complete the flight in VFR conditions. The problem is that you have not validated the forecast. Now let’s add one thing. The most current weather available for your destination at 11 a.m. is 2500 scattered, 4500 OVC and 5 miles. With this information you can now validate the forecast. I hope this brief example shows you that the weather is deteriorating more rapidly than forecast, and at your planned ETA of 2:30 it could be very marginal VFR, or even IFR. This is what I mean by validating a forecast. Your weather analysis is not complete until you have done this.

One of my favorite products from a computer-generated briefing is called Weather Trends. This is not included in a standard route briefing but must be requested separately under selected weather products. What it gives you is the METARS for a given station for the past three hours. Thus, you can compare the actual trend of the weather to the forecast, and more accurately validate that forecast. Other reports that are valuable in validating forecasts are Pilot Reports, and Radar Summaries.

The information is available for pilots to get all they need to make intelligent go-no-go weather decisions. However, the pilot must learn what is available and how to use it. The answer to this is to practice. If every pilot drew up two weather briefings a week and studied them, all would become safer pilots. The key ingredients are knowing what is available, and the ability to validate the forecasts. With a little practice you might find it is fun trying to outguess the weather guessers and, yes, even satisfying.